A Tangent on: Lumberjack Lore

In the early-to-mid twentieth century, several books were published documenting a set of monstrous creatures — known collectively as the “fearsome critters” — which were allegedly encountered with some regularity by the lumberjacks, hunters, trappers, surveyors, and other professionals of the North Woods. Their role in the culture of the scattered logging camps — or at least the understanding adopted by the folklorists who wrote these books — is well summarized in the slanderous title of Vance Randolph’s 1951 text We Always Lie to Strangers. According to Henry H. Tyron’s Fearsome Critters (1939), a newcomer could expect to be the object of a well-rehearsed conspiracy, starting with a “colorful bit of description” concerning some fantastical animal and a corroborating account of personal experience provided by some other resident of the camp. The solemnity, the points of emphasis, the cadence and structure of the story, along with the occasional question thrown to another tired logger siting around the fire and the gravity of the simple nod given in response, were more than enough to convince the stranger that the animal in question was real. And yet, try as they might, these tactics did not seem quite so affective when applied to the dashingly clever folklorists.

All this would be rather amusing (and, indeed, this is how the folklorists portray it) if it weren’t for one series, inconvenient fact: as any person who has spent any significant amount of time at work in the North Woods can tell you, the fearsome critters in these books are 100% real. The loggers sitting around those rustic, smokey fires were not trying to prank their guests, but warn them of the dangers and confusions that they might encounter on their travels. Were the stories entertaining? Sure, but is there a better way to grease up the memory than with a little entertainment? And wouldn’t you want your memory intact when encountering something for which experience has not prepared your muscles?

So please, gather around this digital fire and read carefully, especially if you plan to take a job or go for a visit in the Great North Woods. Learning the truth now will save you the confusion, inconvenience, and yes, even danger, of being unprepared.

1. Agropelter:

The most dangerous thing in the woods is not a bear or a moose or a panther — it is chance, hurried along by the intolerable strain of dripping water or wicked gusts of wind. Especially after a big storm, it is important to walk carefully with an eye to the canopy, looking out for loose branches that could fall on your head with a little extra push from the wind and rain — or the whip-like throwing arm of a large ape, known by centuries of woodsmen as the agropelter. These highly territorial critters make their homes in the hollowed-out interiors of dead snags and feed primarily on the woodpeckers and owls which share this habitat. They guard these snags jealously, hurling massive branches on top of those unlucky enough to pass beneath, causing a small portion of those deaths usually blamed on gravity and mathematical probability. So impressive is the aim of an agropelter that I have only met one person who has been attacked by one and lived to tell the tale — a certain forger who provides mushrooms and fiddle heads for the restaurants around Bartlett, New Hampshire, who told me he was once looking for bear-tooth claw on a dead beech when he was struck by a branch so rotten that it exploded on impacting his shoulder. Uninjured, he turned around just in time to see an ape-like creature with long arms swinging off through the twilight green.

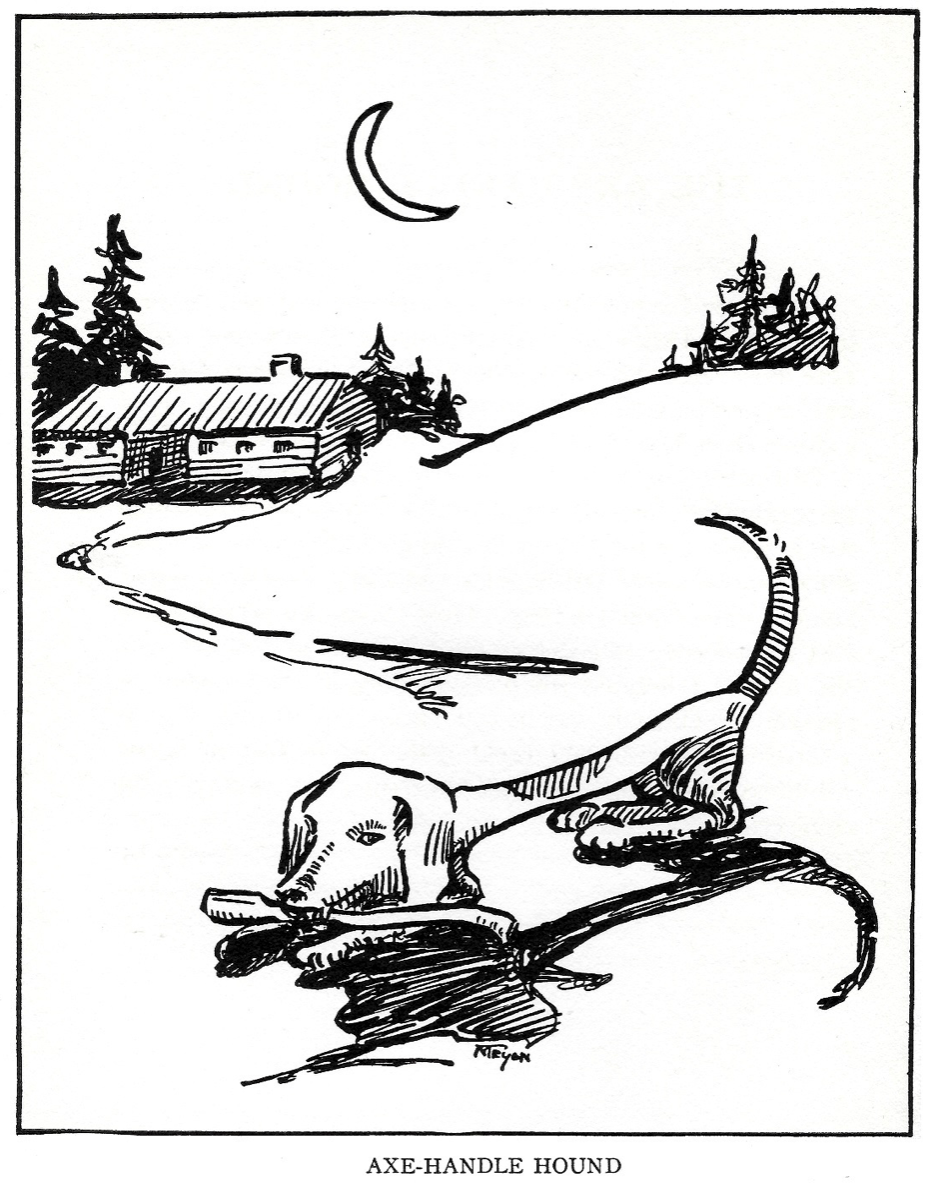

2. Axe-handle Hound:

Not so dangerous as the agropelter, but much more common and quite a bit more inconvenient, is the axe-handle hound. As the name implies, this short, skinny canid is known for raiding campgrounds at night and consuming any axe-handles that it finds unattended. Like the more well-studied chimney swift, the hound’s dependence on a particular human artifact has left it vulnerable to changes in technology and fashion, particularly the introduction of industrial logging and the replacement of wooden axe-handles with ones made of fiberglass, steel, and plastic. And yet, in spite of these challenges, the axe-handle hound is more common than ever, having apparently adapted its diet to include a range of materials which humans of various professions and hobbies might bring with them into the woods. I myself have lost sample vials, pencils, drill bits, and calibers to individuals across New England. While visiting the Fisher Museum at Harvard Forest a few years back, I met a graduate student who claimed to have dissected one of the beasts and discovered an organ similar to those found in certain electric fish, which she suggests may be used to sense the brain patterns of a wondering mind or daydreamer, whose possessions might be more easily snatched. This, I think is rather absurd, given the number of times I have been the victim of a hound despite not

3. Hidebehind:

I may have misspoken when I said that chance is the most dangerous thing in the woods. This is true enough here in New England, but things get wilder in the moss-dripping labyrinths of the Pacific Northwest, where the terrible hidebehind is said to live. I use this phrase — said to live — because even those few who survive the attacks of this particular creature do not provide us with any description of its features. All that we know is what its name implies — that it possesses near-supernatural speed and stealth, which enable it to quickly hide behind a tree or even the back of its victim each time they turn to try and spot it. There is no evidence that I am aware of attributing this ability to bears, panthers, or wolves, so it is not the reality of the hidebehind that I doubt, but the extent of its range, especially now that New England’s forests have regrown. According to the old stories, the only reason that a hidebehind will break off its hunt is if it smells alcohol, a fact recently confirmed to me by a Forest Service entomologist, who was kind enough to gift me a large jug of ethanol from her own stock. Carrying smaller portions of this pungent substance in my backpack, I have yet to encounter one of these creatures — though I suppose that may not mean much…

4. Hugag:

Not all fearsome critters are dangerous or even particularly adversarial. Some, like the hugag, are quite majestic, if a bit confusing. At a glance, the hugag is easily mistaken for a moose, though it is in fact much more closely related to the South American tapir. Closer inspection will reveal the key differences between the two beasts — the hugag has feet with four toes rather than hooves, a long tail and upper lip and, most notably, no joints in its knees. It isn’t clear what evolutionary advantage this provides, though some scientists have speculated that stiffer legs could make it easier for the hugag to feed in fast moving streams. In any case, their lack of joints makes it impossible for the hugag to lie down in the manner of most large herbivores and so they typically sleep leaning against a sturdy tree. According to an old hunter I met at the Maine Wildlife Division’s western field office, this habit is the key to harvesting one of these critters, which are surprisingly quick and secretive. With a little scouting, a hunter can discover which trees their quarry is using and notch them with an axe. When the hugag leans against the tree, it falls and pins the hugag beneath, where it remains until the hunter returns to dispatch it. For those who prefer a less visceral encounter, there are a few moose tours in the northern New England states for which the hugag is a kind of secret menu item. Simply slip your guide an extra ten dollars and they will take you past a few stream side hobble bush patches where, if you are lucky, you may catch a glimpse of one slowed by the thicket. Just remember that the “95% chance of seeing a moose” guarantee does not hold for hugags.

5. Sidehill Gouger:

Another specialist with a peculiar adaption to its chosen habitat, the sidehill gauger is distinguished from other foxlike canids by the arrangement of its limbs. Over the course of many millennia stalking the steep foothills of the eastern United States, it has developed legs that are longer on one side than on the other, allowing for easier travel along a slope. Gougers are generally solitary animals which only seek each other out during the mating season, a task which is made easier by the alternate arrangement of the legs which is typical, though not exclusive, of male vs. female individuals. Some gaugers (perhaps 10 to 15% of the population) are born with the typical limb arrangement of the opposite sex and, during mating season, will form short-term, but very close same-sex pair bonds with typical-legged individuals. When two such pairings meet (one with two males and one with two females), they join together into a loose pack and leave their former territories behind. When they inevitably come across flatter terrain, which their uneven legs make it difficult to cross, they lean against each other, with the right-legged member of each pair providing support for the left-legged member and vis versa. When the pack arrives once more in hilly country, far from their original territories, they pair off in opposite sex unions to produce their pups, then stay together as a single unit to raise them. It has been suggested by the Yale ecologist Bill Ericsson that this behavior boosts the genetic diversity of newly established populations and improves the chances of pup survival in an unknown environment.

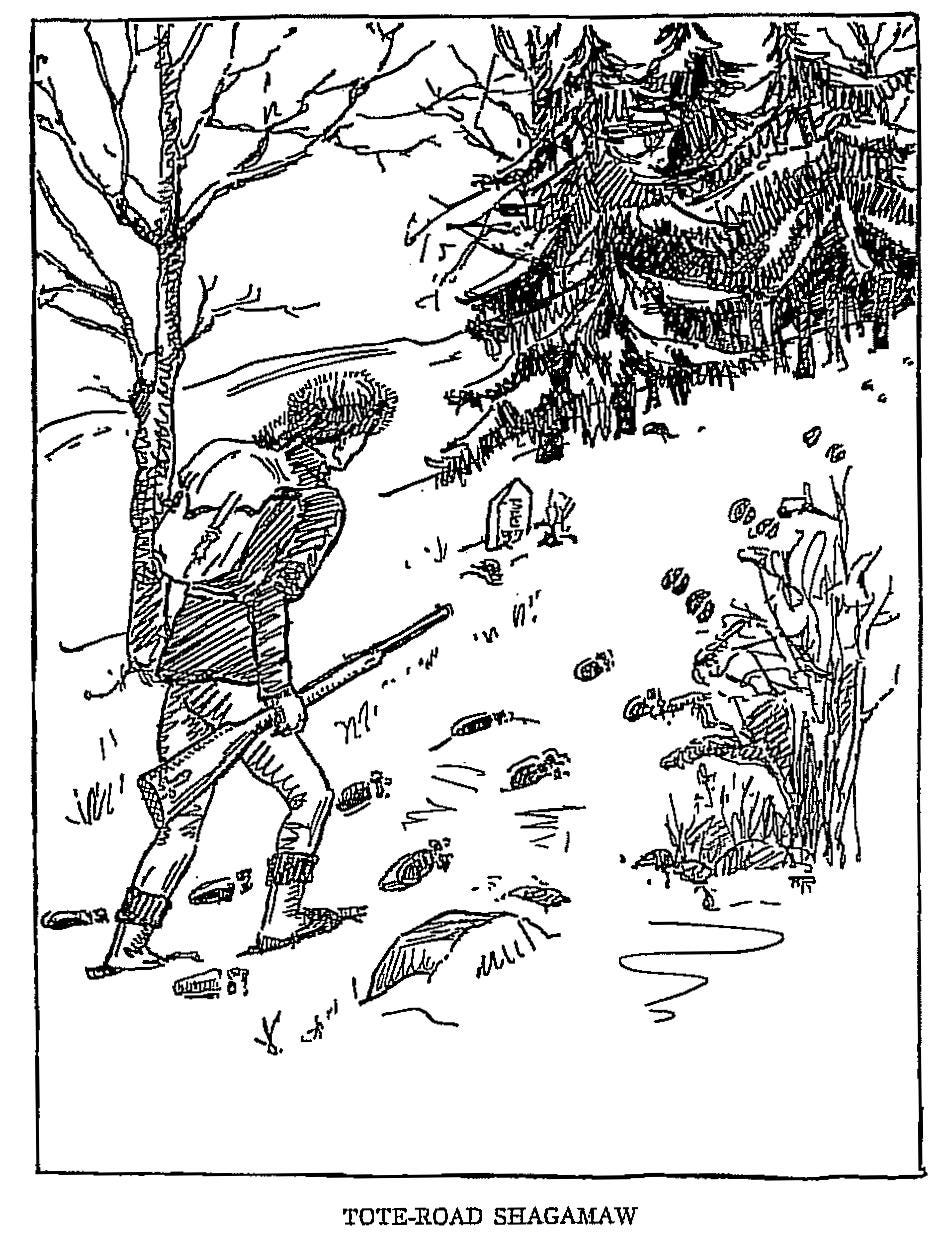

6. Tote-Road Shagamaw:

Many blossoming friendships have been turned to long simmering annoyance as a result of arguments over the proper identification of tracks in the snow. In the wilderness of the great white north, knowing how to read animal signs can be a matter of life and death and it is a skill that many pride themselves on. Challenging that skill is not taken lightly, even if external appearances remain calm. One animal which has been the unwitting cause of many such arguments is the tote-road shagamaw, a cryptic beast of several, equally vague, equally unreliable descriptions. What we do know is that the shagamaw is bipedal and has the hoofs of a moose on its hind legs and the paws of a bear on its front legs. The creature moves carefully through the forest in a straight line, each stride about a yard in length. When it has traveled a quarter of a mile walking on its hind legs, it vaults forward and begins to walk on its hands, creating a confusing artifact in the snow where moose tracks seem to suddenly switch to bear. Explanations for this behavior abound, but the most common has it that the shagamaw is an imitative creature which, upon observing a number of surveyors and trappers pacing careful lines through woods, decided to try for itself. The switch between walking on its hind legs and its hands marks the 440th step of its transect and the highest number to which it can count before having to start over. However one might feel about this story (personally, I’m a bit skeptical), the shagamaw’s apparent love of surveying is undeniable — many a times have I returned to inventory plots after some time, only to find the flags corrected and the ground covered in a confusion of tracks.

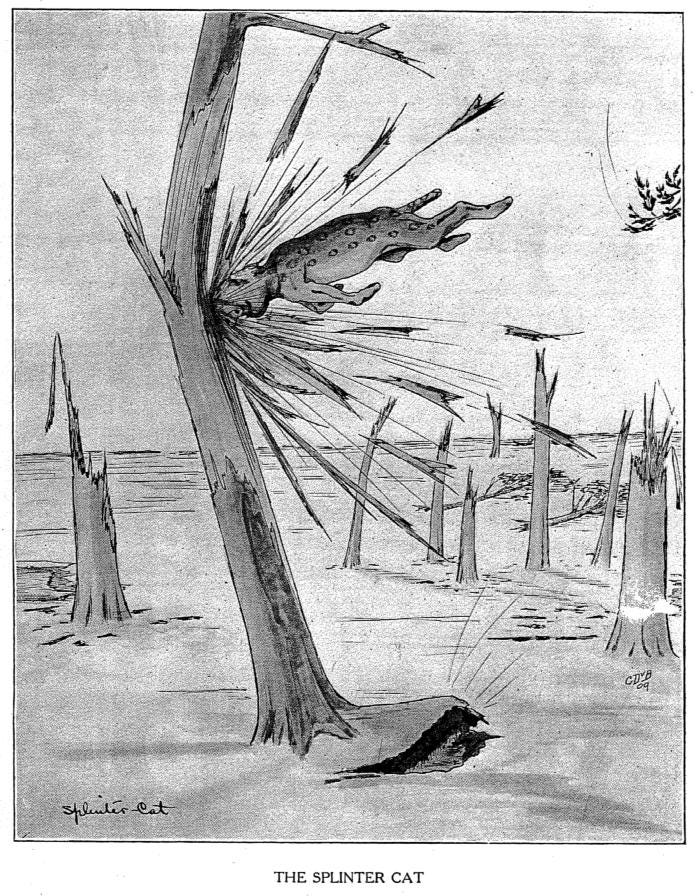

7. Splinter Cat:

It is said that of all the varmints persecuted by early Puritan settlers of New England, none were despised half so much as the splinter cat, the peculiar habits of which quickly became a symbol of Nature’s incomprehensible resistance to improvement. Indeed, suspicions about many of God’s elect were falsely confirmed in the eyes of the congregation as a result of the animal's activates. In those early days, some respected gentleman would often return to town with news of a massive stand of white pine — wooden gold for English shipbuilders — only to return the next day with a work crew to find a glade of broken snags. Luckily, before these unfortunate gentlemen could be cast out for bearing false witness, the cause of the strange phenomenon was discovered to be a hunting splinter cat, hurling itself through the air and headfirst into the trees where its prey lay hidden. Unable to bare the destruction of any monetizable assets (especially wood, which was in such short supply in their homeland), the bounty hunters of Massachusetts Bay wiped the splinter cat from their colony and, later, from the whole eastern United States. Despite this, many still claim to see splinter cats in New England, claims which I personally doubt highly, at least when it comes to the southern part of the region. That splinter cats could one day recolonize the area is not impossible (a single individual killed while attempting to fling itself across Route 15 was found to have wondered all the way from the Black Hills), but all alleged photographs I have seen have been of bobcats, and besides, in a place so densely populated as this one, some qualified state biologist would surely have seen one hurling itself against a tree at Franklin Swamp or Sessions by now.

8. Flitterick:

While New Englanders generally do not need to worry about flying cats, they should still keep an eye on the sky, lest they miss the ariel feats of the flitterick. While superficially resembling a flying squirrel, the flitterick actually belong to its own unique family, which appears to represent a kind of missing link between rodents and bats. Like in the flying squirrel, a loose membrane of skin stretched between the flitterick’s legs allow it to glide through the air. It uses this ability, however, not just for simple travel, but for hunting in a manner similar to that of a peregrine falcon — perched up in a tree or on a cliffside, the flitterick dives down upon its prey at extreme speeds, using its skin flaps to control speed and direction. According to the old stories, flittericks could at times gain so much speed that they were able to kill oxen by passing through their skulls and may even be able to reach these speeds without diving off of a high platform. Fantastic as this may sound, it does appear to be true — as flitterick populations have increased over the past several decades, they have become the number two cause of death for ecologists working with small mammal traps. The most common cause is heart disease.

9. Fur-Bearing Trout:

This one is exactly what it sounds like — a fish covered in hair. There is something about that which is just so funny to me that I cannot think of a way to write this in-character. Just be sure to bring a razor and some shaving cream if your fishin’ up north and want to eat your catch!

Happy Halloween!

For more information on North American lumberwoods folklore and to read some excellent story collections, check out Lumberwoods.org

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment